Meet our artist community: Q&As

Part of an ongoing series, members of our artist community share insights about their work, their stories and their relationship to ACAVA. Visit this page to read more.

Meet Francesca Telling, our artist-in-residence at ACAVA Hosts: Barham Park Studios Residency, a career development opportunity for socially engaged artists from global majority backgrounds. This Q&A will give you an insight into her practice and reasons for joining the programme.

Name

Francesca Telling

Art practice

Interdisciplinary

Would you like to tell us about yourself?

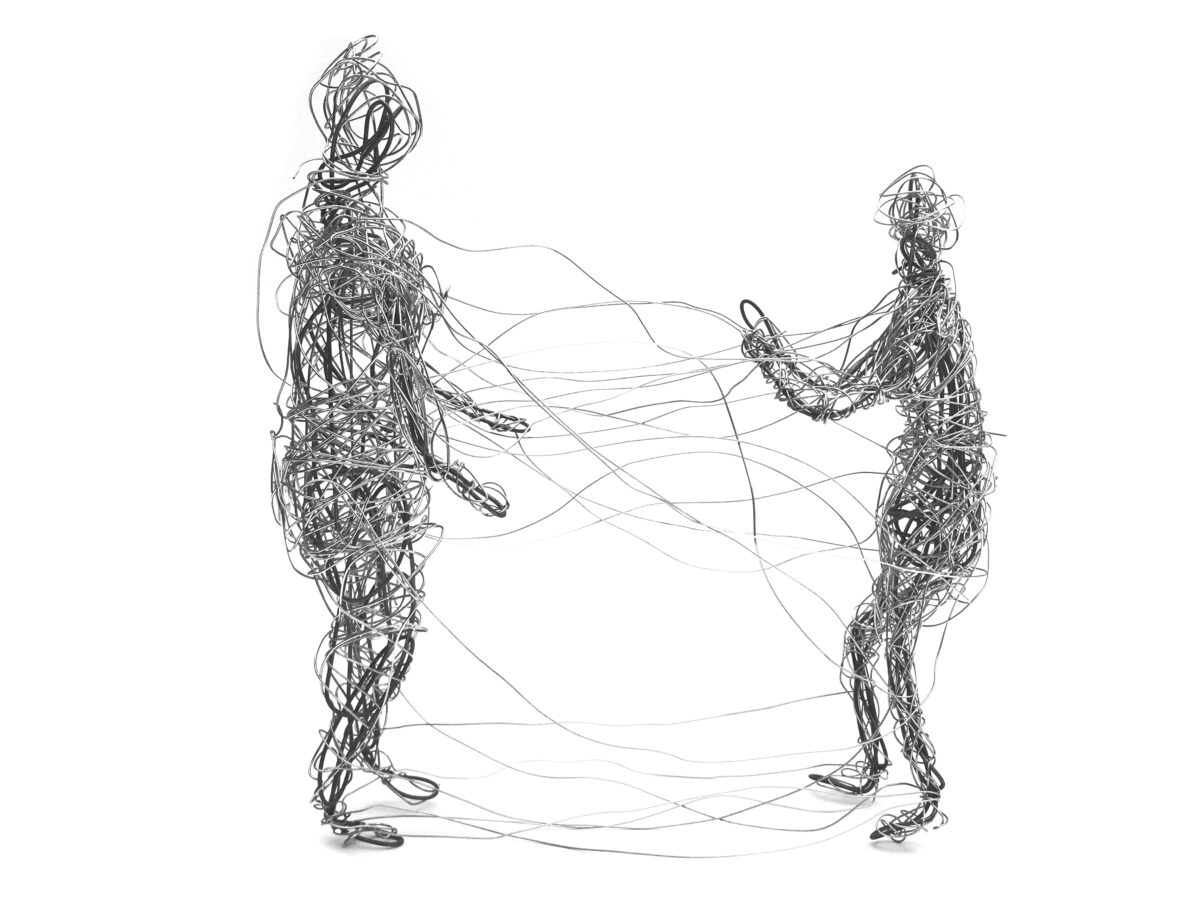

I’m an artist, educational worker and creative learning facilitator. My practice investigates how migration narratives and the social histories of displaced communities are seen in objects and images. I work with sculpture, photography, writing and time-based media to explore cultural loss and grief; and aim to complicate the space between the formal archives preserved by institutions, and informal archives assembled by communities or in homes. My maternal family are Malay-Chinese, meaning that they were Malaysian nationals of Chinese heritage, and I grew up around the suburban parts of South-East London.

Can you tell us about your career leading up to the ACAVA Hosts: Barham Park Studios Residency?

I did an art foundation at Kingston School of Art, then graduated from Fine Art at Goldsmiths University in 2021. Since then, I’ve taken part in two very different alternative education programmes – Conditions, an artist studio with incorporated critical support, and more recently School of Speculation, a four-week spatial practice and research development programme. I’ve been involved in a few group exhibitions and also worked on some collaborative writing and publications projects.

Since graduating most of my time has been spent working in facilitation, usually based in formal educational environments with children, young people and students from marginalised communities. Developing this practice began through working with A Particular Reality, which is a university-based collective focussed on anti-racism in art and education. Through this role, and other roles I’ve taken on since, I’ve facilitated lots of workshops, supported research projects, curated event programmes and worked with other artists and organisations to develop collaborative and social justice focussed projects.

Why did you apply for the residency?

I applied to the residency because I’d been working for a while on a project focussed around local history in Brent, and I felt it was important to base myself in the area during this research period. Specifically, I’m looking at local histories of anti-racism and BIPOC led activism in Brent. This is mainly focussing on material in Brent Archives, connected to the strike led by South Asian women at Grunwick Film Processing Laboratories, and the Development Programme for Educational Attainment and Racial Equality. I see this as a long-term project I’ll be developing over the next couple of years, which explores the expanded idea of ‘representation’ through three threads – photography, archives and unionisation. I’d like to work collaboratively with BIPOC and diaspora individuals working in the archives sector, and use photography as a tool for participatory research around local history and labour rights with young people.

I thought this residency would be a good starting point as it’s for an artist with a socially engaged practice. In 2020 I lived in Brent, just a couple of roads away from the site of the Grunwick Strike, and I’ve enjoyed being able to deepen my familiarity with the area, its history and its community.

Are there any defining moments of your life that have led you to where you and your practice are now?

I think a lot of my practice and the way I think through objects and images has been influenced by the domestic environments I remember from my childhood. My grandmother’s house was very distinctly the home of a diasporic Chinese person, where traditional and heirloom objects sat alongside kitsch chinoiserie, and westernised versions of the ceremonial and superstitious parts of ESEA cultures. You could also observe in the house a tendency to gather and hoard stuff, and I think this paranoiac relationship to material possessions often emerges as a direct response to the grief and loss that comes with migration. In my work I aim to express what it means to collect and categorise things, to find meaning and value in them.

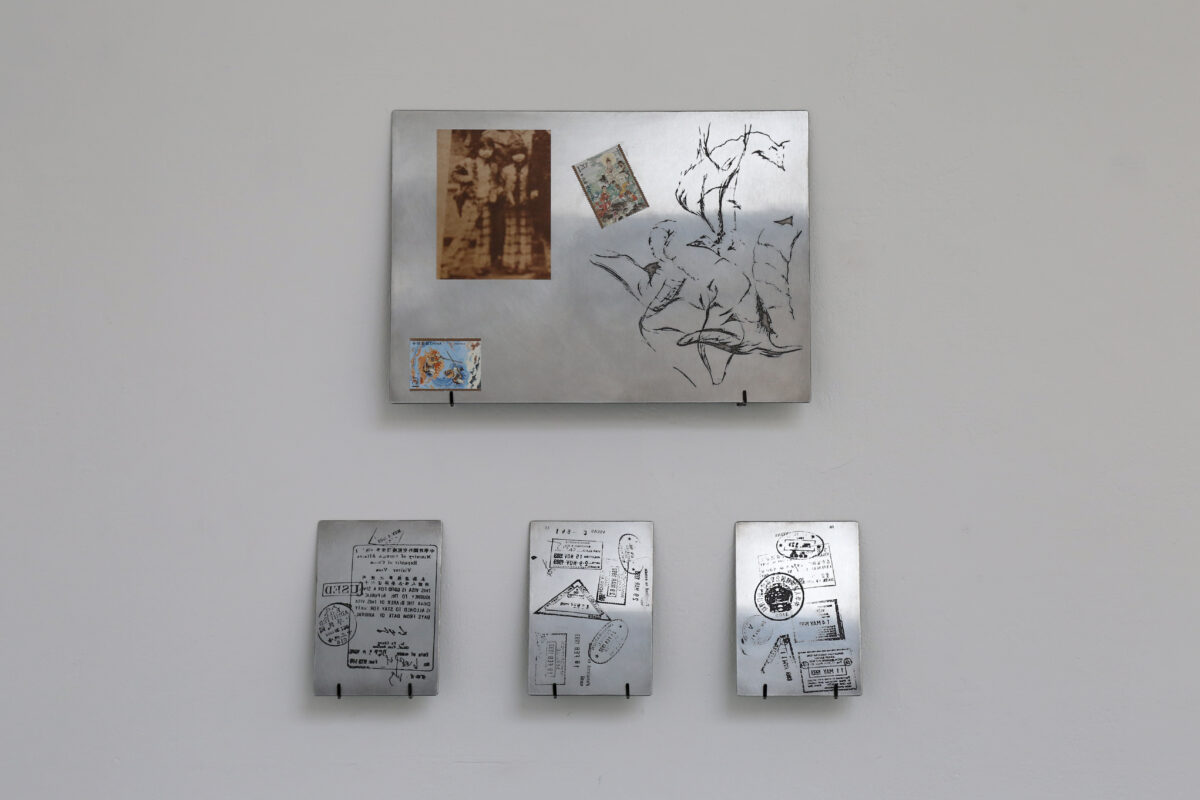

In my practice, I conduct a lot of research in archives, and I’ve spent a lot of time in the National Archives, with material known as the ‘migrated archives’. This collection of documents is the surviving records of Operation Legacy, a strategy deployed by the British government to avoid accountability for the atrocities committed in colonisation – through the burning, destruction and concealment of incriminating material. A section of this collection relates to the Malayan Emergency, and the strategies deployed by Britain to suppress independence movements in Malaysia where my Grandmother was born.

I’m deeply influenced by how ephemera can be a record of the traumatic experiences of displacement and destruction, and the ways we seek a sense of home amidst this. In my practice, I try to complicate conceptions of who and what can constitute an archive, by tracing narrative lines between institutional heritage spaces, and the making and unmaking of informal archives in the family or community.

What are you working on in your studio?

I’ve been working on a lot of different things since moving in. I’ve been making noise-based objects around memory, music and public order – such as a type of children’s toy drum called a bolang gu that plays itself through a programmed motor, and a song used as a timer in rice cookers, which is recorded onto a reel-to-reel tape installation that plays in hour intervals (like a clock throughout the day). I’ve also been making false ‘family photo’ darkroom prints by collaging together images of women in the maternal line of my family.

More recently I am exploring the symbol of fire in relation to archives and possessions. How fire is a destructive force, has been used to erase records of people, histories and wrongdoing. My family were in a house fire in London during their earlier years living here, and this is a story my mum has told me since my childhood. But there’s also a way in which fire can be caring or generative in Chinese culture – joss papers are a type of offering burned for ancestors at funerals and shrines. They represent money, and contemporary forms of joss paper have been made to represent international currencies, technology, luxury cars and designer goods. I’ve been pulping these joss papers and reprocessing them into new sheets of paper to make etching prints on, and casting the pulp into takeaway boxes. I’m thinking about the social histories of economic circulation which emerge through migration and Western assimilation – when they first came to the UK, my family made their money through a Chinese restaurant and takeaway.

If the sky was the limit and money wasn’t an object, what project would you love to work on?

I hope that one day I might be able to get some funding which will allow me to work with the synchronised slide-tape format. This mode of making was prevalent in the 70s and 80s but isn’t seen much anymore. There are some amazing works in this medium – Black Audio Film Collective’s ‘Signs of Empire’ is one of my favourites. It requires a lot of outdated analogue equipment that I don’t have – and also a lot of time on top of that to work out how to use it, make repairs, source obscure parts and materials! But, if I was able to, I think it would really allow me to develop my work between photography, sound and archive in exciting ways.

What materials do you use? What do you like about those?

I work with materials in a way which is responsive to the contexts, histories, use-values and narratives of labour held within them. In the past, materials I’ve used include mycelium, clay gathered and processed from the banks of the Thames, wickerwork, loom weaving, traditional printmaking and lots of found objects.

In my current practice, I mostly use analogue photography and darkroom materials. I like to expand on this through outdated analogue technologies such as slide projection, super 8 film and reel-to-reel tape. I’m interested in how these materials connect to the archive and carry associations with domestic or didactic spaces. When it comes to photography, I am more interested in its historical processes and materials than in taking images – I often work with old negatives and slides which I source from eBay or flea markets.

Do you collaborate with others? Who with and how?

Through A Particular Reality, I work with an extraordinary team of colleagues, who I consider to all be collaborators. Everyone has their own unique practices, knowledges and lived experiences which has deeply impacted how we work as a collective, but also has informed my own work. I am very lucky to have the opportunity to learn from them all, and from the students we support, who are also collaborators! We operate in a non-hierarchical way and really believe in the importance of student voice and active participation in defining what shape anti-racism takes in art and education methodologies. Building from this, I also consider the children and young people I work with as collaborators – when I facilitate workshops and projects we are learning together, and I am very inspired by how perceptive, creative and politically engaged young people are!

How has having an art studio impacted your practice?

For the past year, I haven’t had a studio space, and in retrospect, I’ve realised everything I made during that time was two-dimensional and small-scale. I think these limitations can be generative for your practice, however since having a studio I’ve been able to reengage with working on ambitious scales, making a mess and being noisy. This space to experiment and have failures is really valuable! It’s also about having that separate space to think in, and stick up images and mindmaps all over the walls – it helps me to gather inspiration and develop ideas.

Also, I live in Lewisham, so while my commute to the studio is quite long, I’ve managed to read 6 books on the train since moving in! One of these was ‘Death and the Migrant’ by Yasmin Gunaratnam, which has been really informative towards a lot of my thoughts at the moment.